Premium: On the Launchpad

Yunus Musah chose the United States over three more established soccer countries. We visited Spain to speak to the 19-year-old Valencia midfielder who could be the breakout U.S. star of the World Cup.

VALENCIA, Spain — You can’t help but notice it when you visit the Valencia CF megastore at the Plaça de l’Ajuntament in this sun-drenched city on the Mediterranean. Front and center at the entrance this season is a giant image not of star forward Édinson Cavani or captain José Gayà or coach Gennaro Gattuso, a World Cup winner with Italy. Instead the marquee attraction greeting fans is a 19-year-old midfielder who could be the breakout star for the United States at the World Cup.

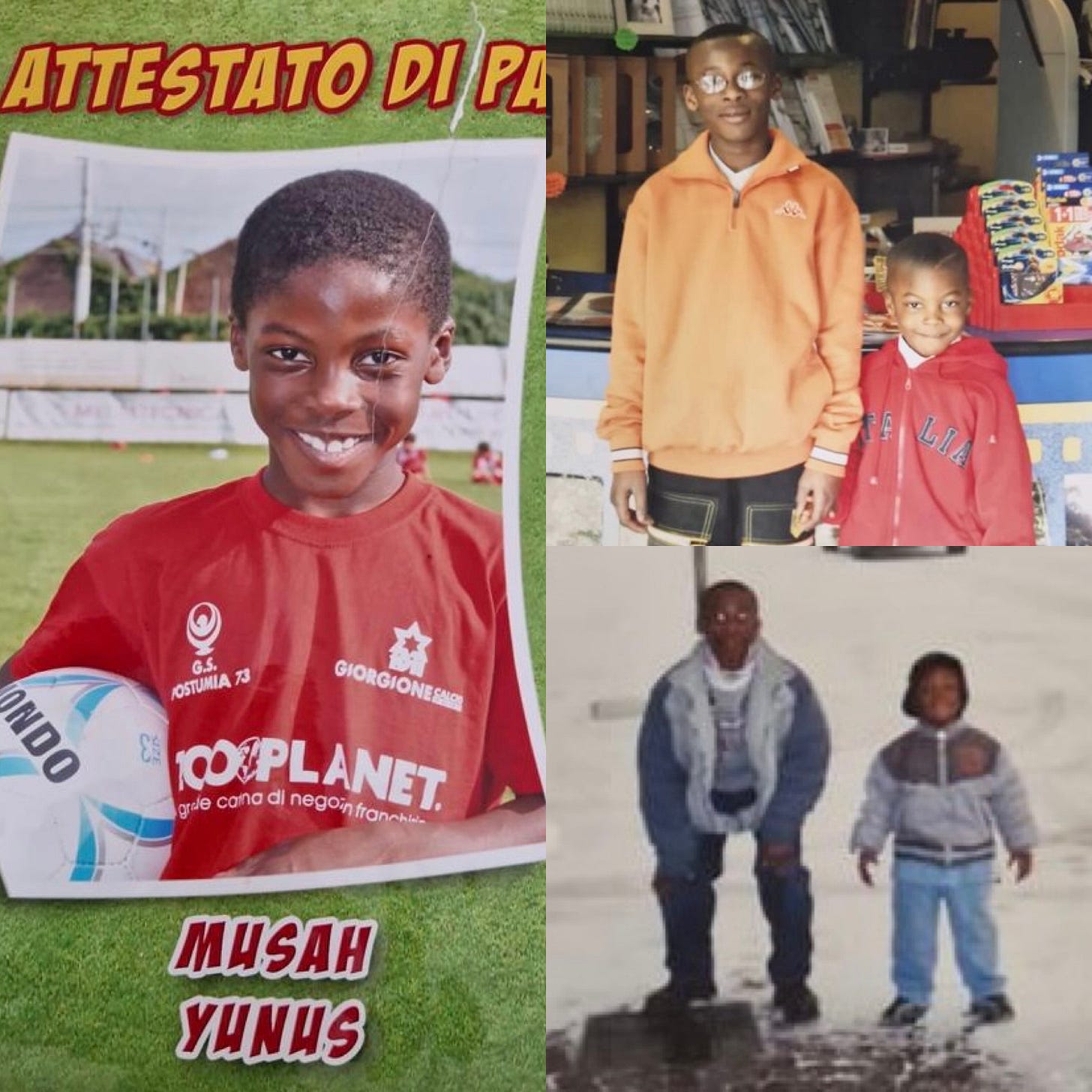

Yunus Musah is a citizen of the world—born in New York City, blood from Ghana, raised in Italy and England, coming of age in Spain—and the global launchpad for one of the USMNT’s first Muslim players may be in Qatar, at the first World Cup hosted by an Islamic country.

“The World Cup has changed so many players’ careers,” Musah tells me during a long interview at Valencia’s training facility, his British accent shaped by seven years of living in London. “And I feel like so many footballers don’t actually ever get to experience the World Cup during their careers. So it’s an opportunity to grasp and to enjoy most of all. But also at the same time really focus and put your A-game out there. Because the whole world’s watching, and anything can happen.”

Musah fell in love with soccer at age 5, playing in a park with his older brother, Abdul, and a friend in Castelfranco Veneto, a small town in northern Italy. They would run around that park for hours during summer days, until they wore down the grass and only dirt remained in front of the goals. Yunus felt an exhilaration running with the ball and knifing through defenders who couldn’t keep up with him. “That was the initial thing that made me love it: doing a mad run and having a shot go in,” he says. “I still love doing that right now.”