A Grant Wahl Bootleg Classic

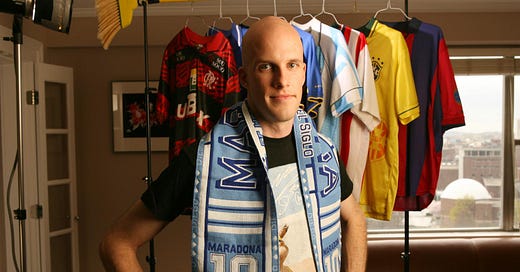

SUBSCRIBER EXCLUSIVE: What happens when a young American embeds with the Boca Juniors ultras? The editors of the new Grant Wahl collection unearthed this gem from his formative early years.

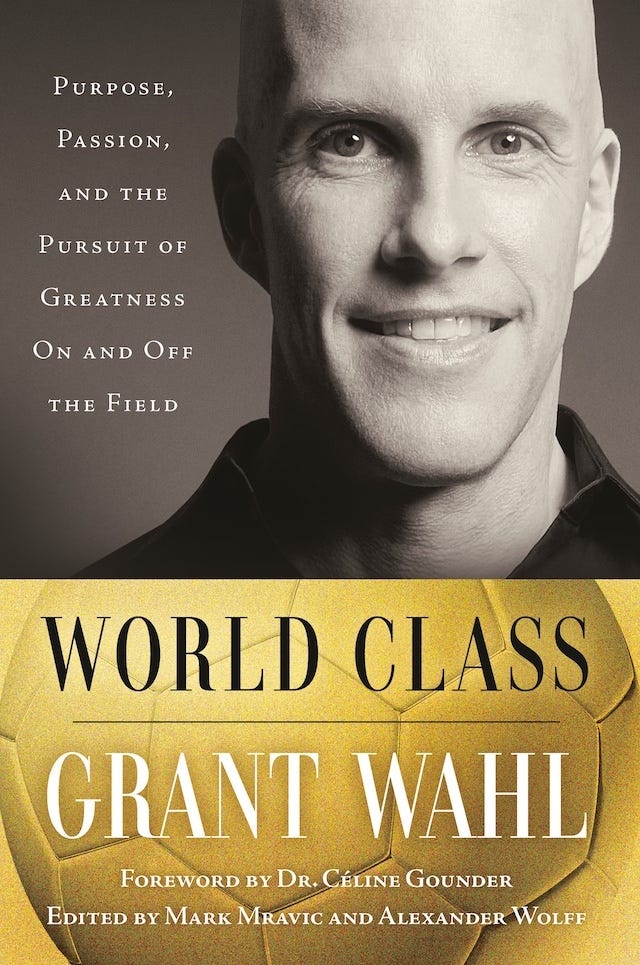

I spent two decades as Grant Wahl’s colleague at Sports Illustrated, and more than a year after his death collaborating with the team that assembled World Class, the collection of Grant’s work that Ballantine Books will publish on June 4. (Available for preorder wherever books are sold.)

For the book, co-editor Mark Mravic and I cast as wide a net as possible over Grant’s work, reaching across sports and story genres to find pieces—on clubs, countries, characters, trends and issues—that best represented the range of the man we regard as a master of the modern craft of sportswriting.

We came to the task with mixed emotions. Of course there was pain and regret that a hard stop had been put to Grant’s life and oeuvre. At the same time there was comfort in being able to return to some of Grant’s most iconic reporting—from his precocious dispatch from the 1998 World Cup after France won on home soil; to that prescient cover story highlighting the teenage LeBron James; to his calling to account the arrogant and powerful, like FIFA and the Qatari regime.

But we also experienced genuinely exhilarating moments of discovery—times we stumbled across something Grant had written that had fallen through the cracks of the years.

Thanks to the Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine, Mark was able to tease out gems from the early days of Sports Illustrated’s website, including Grant’s love note to co-host South Korea during the 2002 World Cup, as well as his reporting on how the Bush presidential campaign tried to use the Iraqi national soccer team, against its wishes, for propaganda purposes during the 2004 Olympics.

World Class also includes pieces from Grant’s college days: an unpublished profile of the great war correspondent Gloria Emerson, his most influential professor at Princeton; and a brave column for The Daily Princetonian in which Grant sounded a rare dissonant note in the chorus of praise after the retirement of longtime basketball coach Pete Carril.

But perhaps our most unexpected find was a long piece Grant wrote for The Vigil, a now-defunct campus publication, which a special collections archivist in Princeton’s Firestone Library helped unearth. It’s an account of three weeks he spent in Argentina, and it showcases the journalistic gifts we would come to recognize in him—a knack for making sharp observations, finding social undertones, sketching nuanced characters and glorying in the pure joy of sport. The piece is reprinted below.

Grant had won a Dale Summer Award, a stipend funded by the family of an alumnus from the Class of 1953, designed to help a handful of rising juniors “pursue worthy projects that provide important opportunities for personal growth, foster independence, creativity, and leadership skills, and broaden or deepen some area of special interest.” The prize allowed Grant to travel to Boston and Buenos Aires over the summer of 1994 to compare fan culture in those two starkly different sporting settings.

As it happened, only weeks before Grant died, the Dale family had reached out to the several hundred beneficiaries of its generosity over the 30 years of the award’s existence to collect memories of those “Dale summers,” as well as testimony about how the experience had influenced the recipient’s life. Gracious as ever, Grant reported back “with such warmth, generosity, and enthusiasm,” members of the family told the Princeton Alumni Weekly in early 2023, “that it deeply touched our hearts.” Here’s a portion of Grant’s letter to the Dales:

First off, a huge thank you to . . . your family for everything you have done for me and for others with the Dale Award. It has had an immense impact on my career and life. In the summer of 1994, I spent three weeks in Buenos Aires and three weeks in Boston doing magazine-style journalism on the people around the cultures of the sports of soccer in Argentina and baseball in Boston. It was my first trip outside the United States in my life. In those days, my career goal was to become a writer at Sports Illustrated.

The trip confirmed for me that I really did want to become a sports journalist writing high-level magazine stories. It also showed me that I could take on ambitious projects and do them well. I ended up going back to Buenos Aires a year later for three months and doing research for my senior thesis on politics and soccer in Argentina. That thesis won the awards given by the Politics and Latin American Studies departments.

Partly with the help of the stories I wrote for a campus publication off my Dale trip, I got an entry-level position at Sports Illustrated as a fact-checker upon graduation in 1996, became a full-time writer at Sports Illustrated in 1997, and ended up spending 25 years there as a soccer writer. I have written two books, including a New York Times bestseller, and for the past year I have had my own subscription writing site at GrantWahl.com. It’s doing well, with nearly 2,800 paid subscribers, and in November I will cover my 13th World Cup (eight men’s, five women’s) in Qatar. The first World Cup I covered was in 1994, when I attended two Argentina games in Boston as part of my Dale trip.

. . . What I can tell you is the Dale Award has had a huge impact on me. And it’s part of the reason I like to spend time advising young aspiring journalists who contact me today. About a month ago, I was in London for a game and met up with a writer I had spoken to back in 2015 when he was just starting out. Now he’s at Sports Illustrated. It was great to catch up with him and be reminded that I can have an impact on young people too.

With World Class, we’re trying to carry forward the spirit of the Dale Summer Award. Proceeds from the book will go toward a fund, named in Grant’s honor and administered by The Daily Princetonian, to cover the travel costs of aspiring student journalists with an ambitious idea but otherwise without the means to report it.

To tide over faithful subscribers to Grant’s Substack until June 4—when World Class appears in stores on what booksellers call “laydown day”—here’s an exclusive look at that piece from the archives, reported during Grant’s Dale summer and published in the December 1994/January 1995 issue of The Vigil. It’s a story that would have gone unwritten if, three decades ago, Grant’s dreams hadn’t met up with the Dale family’s belief in them.

I hope you enjoy this bootleg classic from Grant’s formative years. And that the piece, as well as this backstory of how it came to be, sparks curiosity and empathy, hallmarks of our late friend and colleague. —A.W.

We’re Not in Kansas Anymore: A Weekend on the Road with Argentine Soccer Fans

By Grant Wahl

From The Vigil, December 1994/January 1995

THE SONG begins softly, with reverence, a hymn as we board the Argentina Tours bus. The second time through we clap, the rhythmic percussion animating the tune with a soulful sugar injection. The midnight moon casts a fuzzy blue light through the flags, draped over the windows like a translucent cocoon. With a thump the bus lurches into gear at the start of the third rendition—all twenty men rise from their seats. Fists clenched, they pound on the walls, the windows, the cushion in front of them. Each man belts out the words, their meanings overshadowed by the sheer force of the delivery:

BOOOO-CA, BOCA DE MI VIIIIII-DA,

(Boca, Boca of my life.)

VOS SOS LA ALEGRIIIIII-A

You are the happiness)

DE MI CORAZOOOON . . . .

(of my heart . . . .)

They do not sing the verses; they expel them, so forcefully that I can feel the passion coursing through the hard, bouncing seats. My meek clapping, foreign neophyte that I am, might as well be a whisper, but the regulars turn and smile anyway at their “good luck charm from the north.” For the fútbol fanatics of Boca Juniors, Argentina’s most popular soccer team, anything—a song, a battle cry, even a group trip to the bathroom—can provoke a frenzied celebration. We’re traveling to a soccer match, but the Dionysian intensity of the bus suggests much more. Yells one passenger, pointing to his heart between spurts of song: “It isn’t just a game, it is a feeling. This is our Carnival.”

I had come to Argentina well-versed in the niceties of Kansas City sports fandom, where standing up from one’s stadium seat often constitutes “disorder,” and seventy thousand football fans waving their arms to imitate Native Americans is deemed “rowdy.” In America, supporters of opposing teams coexist peacefully—the excessive distance between cities, along with television broadcasts of games and high ticket prices, prevents the mass buildup of antagonistic forces in the stadium. Profanity in the stands? A definite no-no. The usher will warn an offender only once before removing the heathen from the premises. The working press faces even stricter guidelines—heck, I have been thrown out of a major league press box for wearing shorts (three hours before a game), and there exists a tacit understanding that a journalist may not root for any team.

At my first Boca game in Buenos Aires, after the home team scored a goal, the fellows sitting beside me turned to the mob of five thousand in the stadium’s upper section, gesticulated wildly and cascaded the phrase hijo de puta (PG translation: “son of a whore”) on the visiting Rosario Central fans. Separated by a barbed-wire fence, the Rosario faithful, who had traveled five hours to see the game, returned the pleasantries. When Boca scored again to take the lead, my neighbors leaped in the air, resumed the chant, and banged the signs below us with the ferocity of blacksmiths to an anvil.

This was in the press box.

On the concrete slabs below, behind the goal, la hinchada de Boca, the Boca fans, divided themselves in reactions to the score. Half turned upward to the Rosario crowd and taunted it just as the journalists had, not caring that because they sat directly below their counterparts they would be pelted with small chunks of concrete, food and any other available aerial missile.

At the same time, the other half set off running to the player who had scored the goal, who instead of rushing to his teammates sprinted toward the oncoming frenzied mass. That a ten-foot-deep moat and accompanying fence separated the antagonists only heightened the exchange—player clutching fence, searching even higher than the Rosario section for the power to remove it; fans embracing player, if not physically then spiritually with their unceasing roar. The warning painted on the moat wall read “Do Not Cross—Take Care of Your Life,” which prompted a question. While whose life (the spectator’s) was clearly understood, to what life of his was it referring—his own corpus in the stands, or the players on the field? Soccer is my life. This is our Carnival. Several blue-and-gold-clad fans teetered dangerously over the moat’s edge. Then, just as suddenly, they retreated, the glory only transient, the game not yet complete.

Rosario Central later tied the contest with a last-minute goal, eliciting piercing whistles from the Boca section. Despite the draw, the Boca supporters had given life to “the feeling”—el sentimiento, they call it—in its rawest form. Boca was scheduled to play the following weekend in Rosario. At that moment I decided to travel there with the hinchada.

“Remove your hat,” says Charly when the waiter serves us cold croissants with coffee, a 4:30 a.m. breakfast of sorts at a diner halfway between Buenos Aires and Rosario.

“Excuse me?” The words must be some other part of the local Spanish dialect I fail to understand. After the party on the bus, perhaps he means “Turn your hat backward” or “Explain what the ‘University of Georgia’ on your hat means.”

“Remove your hat,” he repeats. “It is a custom throughout the world to remove the hat when eating.” I look down the long wooden table at twenty now-hatless figures quietly eating their croissants. These are the same people who sang in the bus, who dared the moat? The hat comes off.

Almost afraid to raise my voice, I ask Pablo, sitting across from me, why we are traveling between three and eight in the morning to witness a game that will not begin until nine the next evening. “Because of the murders last month,” he says, barely distracted from his food. “Now the provincial police harass Boca fans more than ever, so we have to travel at night and hope they don’t see us.”

The previous month, two young fans of River Plate, Boca’s archrival, were murdered in Boca’s stadium. The current chief of the hinchada, José Barrita, was suspected of ordering the killings—he and nine of his cohorts fled from police and have not yet been found.

Thus the seeming contradiction—cold-blooded killers who possess dining-room etiquette. It takes Quique Ocampo, who along with Charly is the only traveler over age twenty-five, to correct my assumption. “Only about one hundred of the Boca fans are violent,” he says. “The hinchada is not violence. This”—he points down the table—“this is the hinchada. It is a family.”

Unquestionably, Quique is the patriarch of that family. Now fifty-eight, he pioneered the role of the “professional” fanatic, becoming Boca’s first fan chief in 1967. His responsibilities then included traveling to every Boca game in the world and leading the hinchada into the stadium to the accompaniment of a drum, seventeen horns and a deep repertoire of songs. Since he “retired” from the post in 1980, he runs an eatery full-time next to Boca’s stadium and organizes bus trips to every Boca match in Argentina, ranging from the twenty-minute jaunt to River Plate to the annual twenty-two-hour excursion to Salta, in the north.

Quique is a throwback to the days when fan animosity existed only inside the turnstiles, and then only in a flag-waving, non-physical form. “In the stadium, you are a River fan, I am a Boca fan. There is no friendship there,” he says. “But afterward, outside the stadium, you are my friend.” He emphasizes that no deaths occurred under his regime, and he still cultivates relationships with chiefs of other clubs, who often stop by for food before and after games. Despite the recent trend of violence in and out of the stadium, Quique continues to impart his traditional brand of soccer chivalry to his charges on the bus, primarily through longtime companion Charly, who serves as frontman and fan educator, admonishing us to pay our checks at meals and to silence the singing when we roll by a police car.

At Quique’s call, the group reboards the bus. In the semi-darkness the anthems begin anew. No one sits. This time they all stand in the aisle, jumping and twisting to the beat, hands on the shoulders in front of them, brother connected to brother, moving forward, then back. “BOCA DE MI VIDA!” thunders through the bus while the suspension struggles to contain the repeated landings. Quique presides at the front, using his fingers as a conductor’s batons, then stops to snap a picture.

The thrashing conga line In the aisle only emphasizes that their bimonthly journeys to various stadiums in Argentina satisfy above all a social need, that a Carnival of one would not be Carnival, that a friendship like theirs just might be—no, surely is—the most important thing in these men’s lives. In the still-thriving machismo of Argentina, however, that type of feeling must be professed not to another man, but sublimated to an object that represents them all—in this case, the team. “For a fan of Boca,” says Quique, “Boca is everything. More than your mother, your father . . . ” He furrows his brow, searching for something more meaningful than following his soccer team, then shakes his head. “Everything . . . ”

THE WAIT between the trip and the game is a long one. First we sleep. After rolling into Rosario at eight, the singing halts for four hours, replaced by the equally rhythmic snoring of twenty men in their seats. At noon, we hail taxis in groups of four to transport us to yet another diner, this one in downtown Rosario. Thirty-five years of traveling has instilled in Quique the same routine for each city he visits, partly out of familiarity—one place even serves us on the house—partly out of superstition, which is equally if not more important. As their appointed “good luck charm” for the weekend, I realize that if Boca loses, my friends may not want to continue the new tradition of transporting the Americano, either.

The meal passes uneventfully, except for the five minutes of Boca songs that seem required of every visit to a public place:

. . . ES UN SENTIMIENTOOOO,

( . . . It is a feeling,)

NO PUEDO PARARRRRR.

( . . . I cannot stop.)

O-LÉ, O-LÉ, O-LÉ,

(Olé, olé, olé,)

O-LÉ, O-LÉ, O-LÉ, O-LÁ,

(Olé, olé, olé, olá,)

O-LÉ, O-LÉ, O-LÉ,

(Olé, olé, olé,)

CADA DIE TE QUIERO MAS . . .

(Each day I love you more . . . )

Diner patrons stare at first, then nod their heads knowingly and resume eating—every soul in Rosario knows that Boca plays here tonight. Just before we rise en masse from the table, Quique presents me with a hat to replace the ponderous, already-offending Georgia cap. Below the number twelve, big in blue silkscreen, it reads SIEMPRÉ CAMPÉON (“Champion Forever”). The numeral, of course, signifies the soccer team’s twelfth man, the crowd; to ensure its luck, all of the twelfth men on the trip have signed their names on the hat in white ink. Blue and gold—now I also wear the colors. Their smiles communicate their welcome, and I can’t help but feel a pride of acceptance similar to that afforded a suburban basketball player who can hold his own on the courts of urban America. Though I may not have earned it, I have been inducted into the hinchada.

Hinchada Rule No. 1: Never travel alone wearing Boca gear. To save money and pass the time, four of us walk the two miles back to the bus. We must be taking one of Rosario’s main thoroughfares, for an unending line of cars passes by, each hurling some type of insult against our mothers or our livelihood. We rebuff them with upraised fists and the ever-effective hijo de puta.

Strutting down the street in our blue and gold, we resemble an invading band of outlaws (without sidearms) deserving of some-such sobriquet as the “Boca Four” or the “Rio de la Plata Posse.” On the far left—Diego, dressed in team jersey and distinctive tight-fitting brimmed hat, blue-and-gold braid extending down the length of his back. Also to my left—Pablo, the budding guitar player wearing a sweatshirt of the American heavy metal band Metallica. To my right—Hugo, clothed in a Boca sweatshirt that has seen the wear of five years of soccer weekends. The three young men don’t enjoy their weekday jobs—fry cook, construction worker, sportswear factory worker—but “at least we have jobs,” they say, that pay enough to cover living expenses and the essential thirty-peso bus fee. In the streets of Rosario, however, we are no longer three workers and an American; instead, we are four twenty-year-old hinchas, whistling at women and clicking our spurs in anticipation of the grand show under the stadium lights.

IT IS a comic scene straight out of the movie This is Spinal Tap, when the overzealous rock band becomes lost trying to find the stage in Cleveland. Like a giant rolling megaphone, the bus, windows open, projects the sounds of Boca to the city of Rosario while we drive . . . and drive . . . and drive, crossing the same intersection two and three times. After thirty-five years of this, Quique can’t find the stadium? It seems we have reached a part of town unknown even to him. The driver stops—Quique asks a pedestrian for directions, and we right our course.

Because we arrive late, only an hour before game time, the driver drops us off and proceeds God-knows-where to park. The perk of traveling with Quique and Charly, supposedly, is receiving free tickets from their contacts within the opposing club, Newell’s Old Boys (team names reflect the British influence on soccer). They disappear for the next forty-five minutes, during which time I notice all the seats for the Boca section have been sold.

When they return, they distribute tickets to all but three of us. “They only had seventeen,” explains Charly with a frown. As a result, the trio, including me, has to buy its own seats—in the Newell’s (pronounced “Nools”) section, no less. Charly apologizes, guides us to the entrance on the other side of the stadium, and once again advises me to remove my hat, this time not out of polite correctness but out of common sense—“Take that off, or they will kill you,” he explains. The hat comes off.

Small by American standards, the stadium (capacity: thirty thousand), featuring the requisite moat and fence, somehow allows an extra ten thousand people to fill every aisle, along with some positions on top of the roof. Entering the lion’s den, I check twice to make sure every thread of the blue-and-gold hat remains obscured beneath my sweatshirt. Luis, Jorge and I find unoccupied spots on the grimy concrete aisle steps twenty rows behind the goal.

Every bit as boisterous as the Boca crowd, and larger in number, the Newell’s throng sings its own versions of the songs I have already heard (Boca fans claim to have invented them all). On one side of the stadium, the most vocal of the young men jump up and down with the chaotic cadence of exploding popcorn. Just before the teams take the field, a wave of red-and-black-striped satin momentarily descends over the jumpers. The flag, half the size of a football field, represents only the largest of thousands of its kind attached to concrete, fence, and person, almost all of them personalized by the owner with names (PABLO in large letters), towns (QUILMES, BELGRANO), even politicians (MENEM 1995) and Che Guevara. The red and black may be an orchestrated mass display, but if that be the case, it is groupthink with a personal flair.

While the swearing, fist-pumping and flag-waving flow freely, alcohol does not. The police forbid alcoholic beverages in and around the stadium and do not hesitate to search anyone they deem suspicious. And while some fans surely find ways to imbibe, the predominantly non-alcoholic environment reemphasizes, even validates, the sentimiento fans refer to when they point to their heart, not a beer can, as the source of their feelings. Unlike at an American sporting event, no beer or food vendors roam the aisles. First, there’s no room—people sit in the space available, even on the concrete steps. Second, no one wants to be concentrating on a sausage while the game continues, without stoppage. At halftime, to ease my hunger, I follow a group of fans to the outside edge of the stadium, where a sidewalk vendor selling hot dogs passes one to me through the iron bars.

THE THREE of us sit with the relatively docile members of the Newell’s hinchada, the sixty-year-old men and women who sing only half the songs, who instead of jumping prefer to pump their arthritic fists in unison against the hated blue and gold. The noise, even here, reverberates like an overwatted amplifier without a volume control switch, reaching a pitched crescendo three times in the first half, when Newell’s threatens the Boca goalmouth only to be thwarted by the acrobatic goalkeeper Navarro Montoya.

American sportswriter Frank Deford argues that “frustration is at the heart of soccer. You expend all this energy, and nothing ever happens. Everything is a near-miss.” Yet for each near-miss the crowd reserves that negative energy, piles it upon previous failures, and either transforms that into a wholly positive catharsis (upon scoring) or leaves with a completely negative despondence (by not scoring, or losing). The more frequently a team pushes itself to the brink of a goal and fails, the more voluble the crowd will react to success (or ultimate failure).

This is that type of game. When Newell’s scores the only goal of the contest early in the second half, the already deafening amplitude only increases. Even the elderly rise from their seats during the five-minute celebration of triumph, sport and, above all, identity. The middle-aged man next to me clutches his red-and-black flag and thrusts it to the heavens, as if the Almighty Himself had kicked the ball into the right corner of the net. Eyes closed, he wraps his arms around his wife like a drowning man suddenly thrown a life preserver. This is his Carnival, also.

As if someone has just pressed the giant mute button in the sky, the Boca crowd, singing literally for the previous ten hours, opens its collective mouth but cannot utter a sound for five minutes. The men in blue and gold remain standing, arms folded, no longer twisting and galloping atop the concrete. They don’t even blink.

On the far end of the stadium the mammoth red-and-black-striped flag unfurls again with breakneck velocity, enclosing the frenetic Newell’s fans like a security blanket over a collection of pinballs, uniting the group of eight thousand in a Hades-colored palette beneath the satin. Unseen but not unheard, their chant commands the team to give it:

DA-LE, DA-LE, DA-LE, DA-LE NOOLS!

DA-LE, DA-LE, DA-LE, DA-LE NOOLS!

AAAAAYY, DA-LE NOOLS!

The game convinces me more than ever that the sport may serve as the medium for social gathering, but witnessed by itself, by oneself, it contains no special charm for the lone fan. Luis admits that even if Boca were winning, sitting apart from his friends “just isn’t the same thing.” Frequently I glance through the barbed wire to the nearby Boca section, to the unmistakable tall figure of Diego, arms around Pablo and Hugo, beseeching his team to rally for the tying goal that never comes. The emotions could be found at a rock concert, a political rally, just about any meaningful group setting. But here, under the lights or on a Sunday afternoon, the grand provocateur of communal passions will always be fútbol.

IT WASN’T supposed to happen this way. I wasn’t supposed to get lost in a swarm of Argentines five hours outside of Buenos Aires. At the end of the game I follow Luis and Jorge out the stadium gates, where we meet Charly, who by the speed of his gait is clearly in a hurry to find the bus. Then, all in one second, Luis veers off to pick up a post-game Italian sausage, Charly swerves in the opposite direction for no apparent reason, and Jorge . . . Jorge just disappears.

Perhaps, in their desire to leave as quickly as possible, they forget that this is the American’s first trip with the hinchada. A scarier thought—perhaps the “good luck charm” has been proven ineffective, and they are jettisoning the ballast now. Over the next two hours, I circle the stadium seven times, ask an old man in increasingly delirious Spanish if he has seen any Boca fans (he hasn’t), and witness every single person, including the two teams, vacate the premises.

Finally I resolve to ride a cab to the bus station and catch an overnight back to the capital. Common sense, of course, says that my friends would not just leave their newest hinchada member at the stadium, but common sense does not always reign at times like these. I enter the station, approach the ticket window and feel a pull at my arm. It is a police officer. “Your friends are waiting for you just outside the far door,” she says. I stride down the clean, nearly empty hall toward the short man with grey hair and kind, worried eyes. Quique embraces me, then folds his arm over my shoulder while we walk slowly, without a word, to the waiting bus.

“Thank you for letting me join you this weekend,” I say to Quique, who sits next to me at the diner halfway between Buenos Aires and Rosario. “I had a memorable, fun experience.”

“Fun?” he asks. “We lost. Losing is not fun.” Tears stain his cheeks, which at first I construe as a response to the trauma of my disappearance. Pablo corrects me. “He does this whenever Boca loses.”

Come to think of it, though, winning could not be fun, either, not the way Americans or even Argentines define the word. The emotions manifested before and during every game overpower such feelings—one leaves the contest in wholehearted elation or abject misery, at one of two extremes. Fun is not an extreme word. If that be the case, then, something else must cause the fans to continue traveling in support of their teams, especially those that lose frequently. It is not the soccer itself, not the victories, not a personal love of competition. Rather, it is the human connection—the jumping conga line, the songs in the diner, the posse walking down the street—the genuine fraternal love of their fellow travelers always cloaked in the sentimiento for the team. The feeling that, no matter how bitter a defeat may be, the following weekend brings another Carnival. For its fans, soccer is not so much sport as it is brotherhood and, quite simply, hope.

Argentine author and Borges disciple Adolfo Bioy Casares could just as well have been referring to the followers of soccer when he described, in The Dream of Heroes, another seemingly mundane exercise:

The two of them, as if by agreement, proceeded to pee in the street. Guana remembered other nights, in other neighborhoods, when they had also peed together on the asphalt in the light of the moon: he reflected that a friendship like theirs was the most precious thing in a nman’s life.

Well put, maestro. But could Bioy the artist possibly have known “the feeling” of the hinchada? Certainly. After all, it is said that his second passion, after writing, was watching fútbol . . .